数ヶ月前、渋谷のど真んなかにある高いタワーで開催されたWeb3のイベントに参加していたとき、私は、そこにいた何人かの人びとのあいだの小さな騒ぎを感じた。目の前にはフルートを持った背の高い黒人の後ろ姿があった。世界各地において幽霊が訪れたかのごとき「目撃 」情報は何度か耳にしていたが、私は幸運にもアンドレ3000を目の当たりにすることができたわけだ。もっとも怖気づいた私は舌を噛むだけで、彼に何かしたわけではなかった。だいたい特段アウトキャストのファンではなかった私は、ノスタルジーからスターストラック になったわけではないのだ。彼のことを意識するようになったのは、アウトキャストの最後の2枚のリリースと、その後何年にもわたってアンドレがランダムに発表したゲスト作品がきっかけだ。まあ、いまとなってはファンかもしれない。みんなと同じように私も彼の精神状態を心配していたのだから。

アンドレ3000の17年ぶりとなるアルバムが、パレスチナのガザで大虐殺が起こっているのとまったく同じ時期にリリースされたのは偶然の一致だろう。だが、ほんとうにそうなのだろうか? 宇宙はおかしなものだ。彼は「No Bars(小節はない)」とはっきり言っているので、この音楽のアクアティックな性質に驚く人はいないだろう。瞑想的、アンビエント、シンプル、リラックス、退屈などなど。誰も予想していなかったこのレフトフィールド作品を形容する形容詞はまこと多い。フランク・オーシャンの古典 『Blonde』収録の“Solo (Reprise)”で、息もつかせぬ勢いを見せた男の作品だ。クラシック のさらにそのうえのクラシカル なミュージシャン。

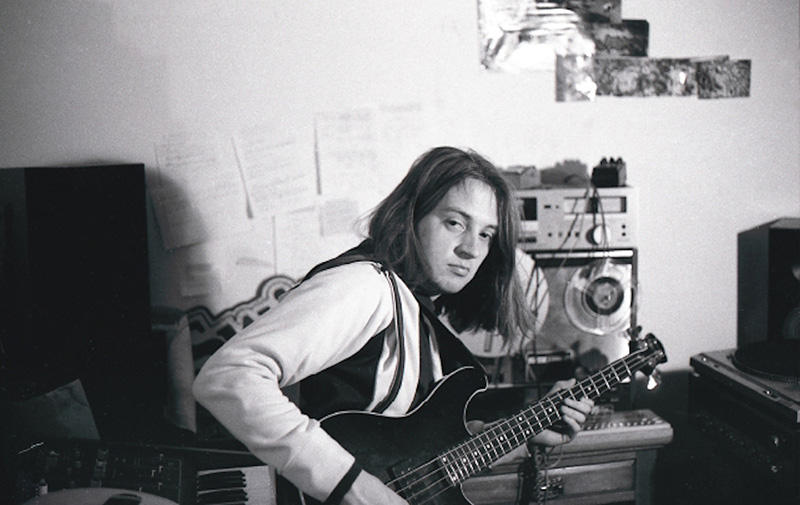

2024年、文字通り指先ひとつでどんな音楽にもアクセスできるようになったいま、1970年代と聞いてもピンとこないかもしれない。ファラオ・サンダースの『Thembi』(1971)を彷彿させる緑色の服を着たジャケット写真は、多くの人が西洋社会の侵略に抗議するために着ていた、インドの影響を受けたスピリチュアルな服装に似ている。だが、そんなことをもう多くの人が理解しようとすることはないし、憶えていないかもしれない。フリー・ジャズやスピリチュアル・ジャズの伝説的なジャズの多くが、高次な意識に到達するためにフルートを演奏していたことを多くの人は理解していないし、憶えていないかもしれない。

『ニュー・ブルー・サン』はラップの世界にとっては驚きだが、70年代のジャズの名人芸を排した黒人的伝統に完璧にフィットしている(インドから音楽的、精神的に影響を受けたことは注目に値する)。マイルス・デイヴィスの『In a Silent Way』を思い出せばいい。絹のようなメロディ、スローモーションのヴァイブ、リズムが飛び込んでくるまでのムーグ演奏によるゴージャスな地図。あるいは、コルトレーンの『A Love Supreme』における感情的な呪文。そして、数多のサン・ラー作品で聴ける、インストゥルメンタル神秘主義の奇妙な響き。アンドレは、経済的な状況を顧みることなく非商業的でエキセントリックな道を受け入れ、かれこれ50年以上にわたって継続されている、フォロワーたちにカーブボールを投げることを決めた黒人アーティストの系譜をたどっているのだ。

各トラックに付けられた凝った皮肉たっぷりのタイトルは、誰もが面白がるだろう(*)。だけどジャズ・ヘッズは音楽のシンプルさにがっかりするかもしれない。しかし、それでいいのだ。皮肉屋は、この太陽の下に新しいものは何もないと言うだろう。しかし、そんなことはない。アンドレ3000のレフトフィールド・リリースは、いまのところ唯一、インスタグラムのストーリーやソーシャルメディア上で伝染していく実験的音楽だ。あたかもビートとフローがあるかのように、ほとんどビートのないニュー・アルバムにうなずくアトランタのヒップホップ・ファンのユーモアを反映したミームがインターネット上には溢れかえっているのだ。CD/レコード店の実験的ジャンルの売り場には足を踏み入れたこともない、つまりこのようなアルバムを手に取ることもないような人たちが、アンドレ3000が作ったこのチルな新世界について、友人たちに(私がそうだったように!)チェックしておくべきだと吹聴しているのは明らかな事実だ。

ときに歴史は繰り返されるものだが、重要なのは文脈なのだ。セラピーの適切さが広く認識されるようになったいま、ブラック・ライヴス・マターであれガザ占領の終結であれ、人びとが抗議のために通りに飛び出す準備が整っているいま、自殺や深刻な精神疾患は治療や予防が可能だと多くの人が感じているいま、『ニュー・ブルー・サン』は、みんなの重たい心を休ませるために作られた、この戦争の年の最後の 鎮静剤 であり目印である。

訳注 *たとえば1曲目は “本当に "Rap "アルバムを作りたかったんだけど、今回は文字通り風が吹いてきた”。2曲目“俗語であるプッシーは、正式表現であるヴァギナよりも遥かに簡単に舌を転がす。同意する?” /**レッド・ピル=『マトリックス』に出てくる現実が見える薬/チル・ビル=リラックス剤。

[[SplitPage]]

Andre 3000 - New Blue Sun

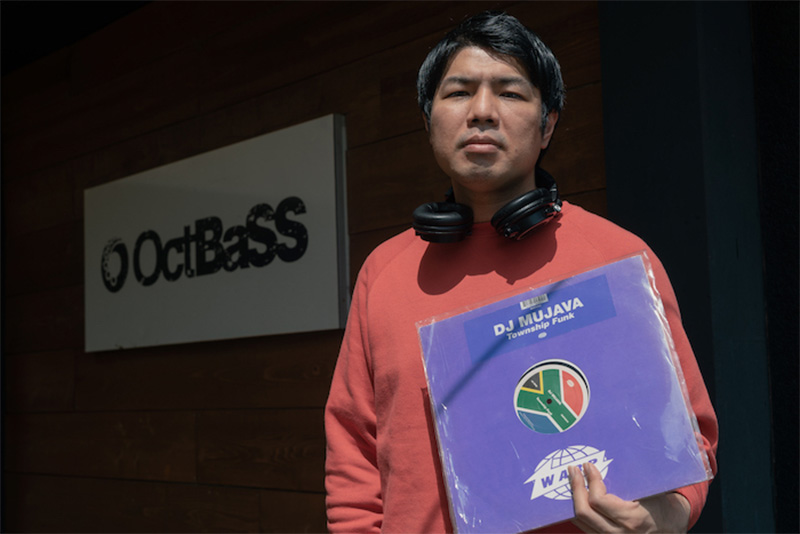

by Kinnara : Desi La

Several months ago, while attending a web3 event in a tall tower in the center of Shibuya, I felt a small commotion among some of the people there. In front of me was the back of a tall Black man carrying a flute. Having heard the stories numerous times of these “sitings” around the world, like a ghost visiting, I was lucky enough to witness Andre 3000 myself. Intimidated, I bit my tongue and let him be. Never an OutKast fan, I wasn’t star struck from nostalgia. I came to him late with their last 2 releases and then the scattered guest drops he popped up on randomly over the years. A fan, yes but also concerned of his mental state knowing other people had similar concerns.

The release of Andre 3000`s first album in 17 years at exactly the same time as a genocide is occurring in Gaza, Palestine is a coincidence. Is it? The universe is funny that way. He's said very clearly “No bars” so no one is surprised by the aquatic nature of the music. Meditative, ambient, simplistic, relaxing, boring, etc. There are numerous adjectives that could be used to describe this left-field work that no one was expecting. This from the man that killed “Solo (Reprise)” on Frank Ocean`s classic Blonde breathlessly. A classic musician upon a classic.

2024 with access to any type of music at ones finger tips literally, heads may not connect the dots to the 1970`s. Or the jacket photo`s resemblance to Thembi by Pharaoh Sanders with green clothing similar to the Indian influenced spiritual garb that many wore to protest the aggressions of western society. Many may not understand or remember that many Jazz legends of free jazz or spiritual jazz took on the flute to reach higher consciousness.

New Blue Sun is a surprise to the world of rap but fits perfectly in the Black tradition of 70`s out Jazz minus the virtuosity (which notably was influenced musically and spiritually by India). You only need to look back at Miles Davis` In a Silent Way. A gorgeous map of silky melodies, slow motion vibes and Moog vistas before the rhythms jumps in. Or the emotional incantations of Coltrane`s A Love Supreme. Numerous Sun Ra albums too many to mention evoke the quirky side of instrumental mysticism. Andre follows a lineage stretching over 50 years of Black artists who decided to throw curve balls to their followers embracing noncommercial eccentric pathways regardless of economic fallback.

The elaborate tongue in cheek titles of each track will amuse anyone. Jazz heads may be disappointed in the simplicity of the music. But that’s ok. The cynic will say there is nothing new here under the sun. But that’s not what is happening. Andre 3000`s left field release is probably the only experimental music that is viral across instagram stories and otters social media. Memes have flooded the internet reflecting humor of Atlanta hip hop fans nodding to the almost beatless new album as if there were beats and flows. Its a clear fact that people who would never venture into the experimental aisle of a music store (if there were one) and pick up such an album are dming their friends (as happened to me!) about this chill new world made by Andre 3000 which I should check out. Though history sometimes repeats itself, the context is most important. In a time of wider recognition of therapy’s relevance, in such a time when people are ready to run out into the street to protest, whether for Black Lives Matter or the end of occupation in Gaza, in such times that many feel that suicides and severe mental illness is treatable and preventable, A New Blue Sun is a red chill pill last earmark in this year of war made to lay everyone’s heavy heart to rest.

__ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __

by Ben Rayner

by Ben Rayner